Introduction to Classical Conditioning

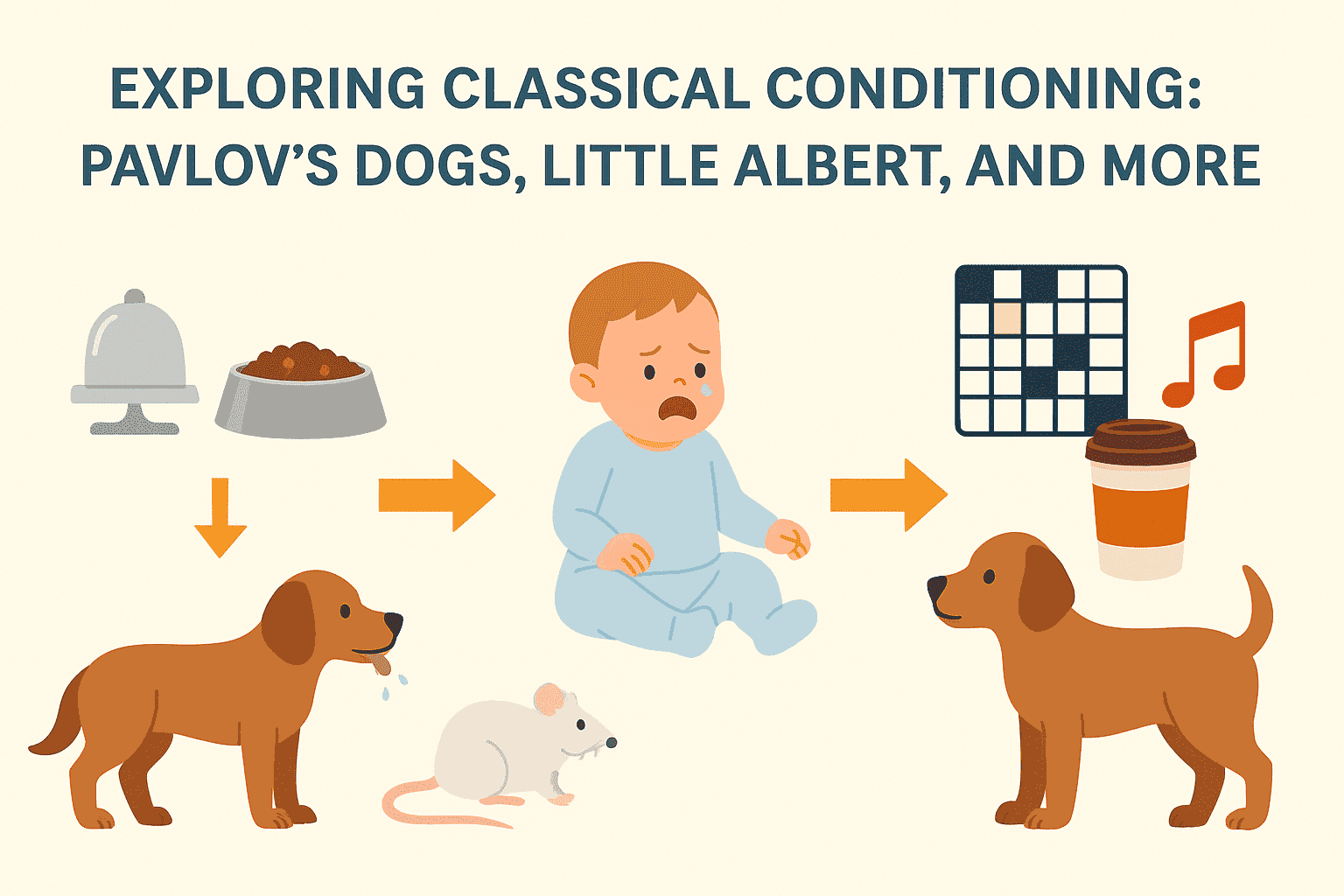

Classical conditioning is a form of learning where a neutral stimulus becomes linked to an automatic response. In this process, a previously neutral cue comes to trigger a reflexive reaction after being paired with a naturally occurring one. Pavlov’s classic experiments provide a clear example: he paired a tone (initially meaningless) with food, and eventually the dogs began to salivate at the tone alone. In fact, Pavlov – while studying digestion in dogs – discovered by accident that his dogs started salivating not only at food but at cues associated with food (like a bell). These findings launched a new understanding of how simple associations in the environment can shape behavior.

Pavlov’s Dogs Experiment

In Pavlov’s experiment, the setup was straightforward. Food served as the unconditioned stimulus (US) that naturally produced salivation (the unconditioned response, UR). Pavlov introduced a neutral stimulus (NS) – the ringing of a bell – which initially caused no salivation. During conditioning, Pavlov rang the bell immediately before giving the dogs food. After several pairings, the bell alone (now a conditioned stimulus, CS) caused the dogs to salivate (the conditioned response, CR).

-

Before conditioning: Food (US) → Salivation (UR); Bell (NS) → no salivation.

-

During conditioning: Bell (NS) + Food (US) presented together; dogs salivate to the food (UR).

-

After conditioning: Bell alone (CS) → Salivation (CR) (the bell now triggers the response).

Pavlov also noted related phenomena. If the bell was repeatedly sounded without food, the learned salivation would fade away (extinction). He observed that dogs sometimes salivated to sounds similar to the bell (stimulus generalization) and could learn to respond only to the specific bell (stimulus discrimination). In sum, Pavlov’s work demonstrated the basic rules of classical conditioning: a neutral cue (bell) can become a signal for a reflex (salivation), producing a learned response.

The Little Albert Experiment

John Watson and Rosalie Rayner extended classical conditioning to human emotions in their famous “Little Albert” study (1920). They worked with an infant, “Little Albert,” who initially showed no fear of animals. Watson used a white rat as the neutral stimulus (NS) and a loud noise (hammer striking a steel bar) as the unconditioned stimulus (US), which naturally made Albert cry (unconditioned response, UR). They repeatedly presented the rat (NS) paired with the noise (US). After just a few pairings, Albert began to cry at the sight of the rat alone – the rat had become a conditioned stimulus (CS) eliciting fear (conditioned response, CR).

-

Initial state: Albert had no fear of a white rat (NS).

-

Unconditioned stimulus: A loud noise (US) naturally caused crying (UR).

-

Conditioning process: Each time Albert saw the rat, the experimenters struck a bar to make the noise. After several pairings, Albert began to expect the noise when he saw the rat.

-

Outcome: Albert cried when he saw the rat alone (the rat had become the CS).

-

Generalization: Albert’s conditioned fear spread to other white, fluffy objects (e.g. a rabbit, a fur coat, even Watson’s Santa Claus beard). This showed that fear learned in one context could extend to similar stimuli.

This study illustrated that an emotional reaction (like fear) can be classically conditioned in humans. Watson’s work was groundbreaking in showing how phobias might be acquired through simple associations. (Of course, by today’s standards the experiment raises serious ethical issues, since Albert’s fear was never fully undone.)

Mary Cover Jones and Little Peter

In the 1920s, psychologist Mary Cover Jones turned classical conditioning into a therapy tool. She worked with a three-year-old boy nicknamed “Little Peter,” who had a severe fear of white rabbits (and similar soft, furry items). Jones hypothesized she could eliminate his fear by reversing Watson’s procedure: pairing the feared object with something pleasant.

-

Subject: Peter, a three-year-old boy with a phobia of rabbits and related items.

-

Counterconditioning: Jones brought Peter into a room where a white rabbit was present at a distance while he ate his favorite candy. Other children in the room, who were not afraid of the rabbit, played around him. Over several sessions, the rabbit was gradually moved closer as Peter continued to receive treats, so that the rabbit was paired with a positive experience rather than fear.

-

Outcome: Peter’s fear steadily diminished. Observers recorded that his reaction improved “from almost complete terror at sight of the rabbit to a completely positive response with no signs of disturbance”. Eventually Peter could touch and pet the rabbit without crying.

-

Significance: This “unconditioning” demonstrated that classical conditioning could be used to eliminate a learned fear. Jones’s experiment laid the groundwork for behavior therapy techniques like systematic desensitization.

Broader Impact on Psychology and Learning

These landmark experiments had a profound influence on psychology. Pavlov’s work provided the basis for the behaviorist movement, which held that all learning results from associations in the environment. Watson extended this idea to humans, arguing that even emotional reactions like fear were learned. In effect, psychology shifted to focus on observable learning processes rather than introspection.

Classical conditioning principles remain important today. In therapy, for example, exposure therapy uses conditioning to help people unlearn fears: a person is gradually exposed to a feared object without any negative consequence, so that the fear response is extinguished. Conditioned aversions are also used in treatment: the drug disulfiram (Antabuse) makes drinking alcohol trigger nausea, creating an aversion to drinking. In education and advertising, professionals pair desired stimuli with positive images or music to create favorable responses (for instance, associating a product with enjoyable scenes).

Another striking example is taste-aversion learning. Researchers have shown that animals will strongly avoid a food after just one pairing with illness – a one-shot conditioning. In practice, ranchers have poisoned sheep meat so that coyotes later avoid sheep altogether. These examples demonstrate that classical conditioning rules apply far beyond the lab. As one review notes, Pavlov’s discoveries “formed an essential part of psychology’s history,” helping make the discipline what it is today and continuing to shape our understanding of behavior.

Conclusion

Classical conditioning experiments showed that many behaviors and emotions are learned through association. Pavlov’s dogs learned to salivate at a bell, proving that a neutral cue can trigger a reflex once it is consistently paired with food. Watson’s Little Albert showed that even fear can be conditioned in a human child, and Mary Cover Jones’s Little Peter study proved that such conditioned fears can be unlearned. Together, these studies underscore a powerful truth: much of learning in animals and people comes from the connections we form between events. The legacy of these experiments is enormous, as classical conditioning remains a cornerstone of learning theory and continues to inform everything from therapy to advertising.

Sources: Foundational studies and reviews in psychology and neuroscience, ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, verywellmind.com, en.wikipedia.org, psychclassics.yorku.ca